Education has been a major concern to the American people for a long time. A large emphasis is placed on how American students are performing in the classroom, and when their scores or graduation rates are down the country looks for a reason why. More often than not, the most common reason offered is that we are not spending enough money on our education system resulting in missed expectations. In 2015 the total federal spending on Education was 102.26 billion as compared to other large budget categories such as Military 609.3 billion, Medicare 1.05 trillion and Veteran’s Benefits 160.63 billion which excludes State and Local spending on Education (which is nearly 1 trillion). Some states, like New Jersey, are looking to make big changes on how they distribute funds to schools. Are we not providing enough money to our education system or have we simply made the lack of money a scapegoat for the real issues? What has become apparent though is that no research supports that money increases test scores and graduation rates.

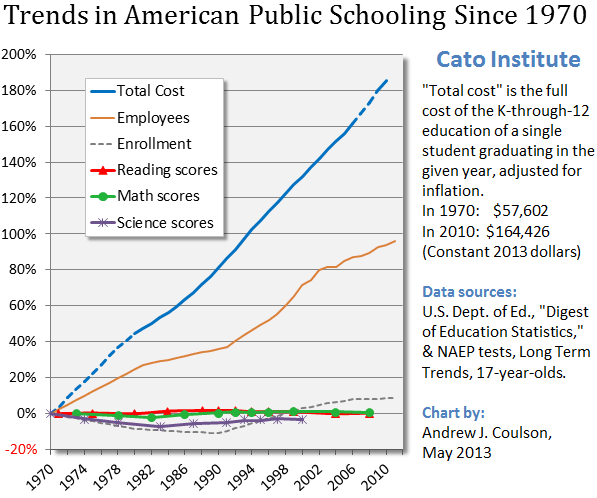

The Cato Institute’s Andrew J. Coulson demonstrated in the chart (shown below) that even with increased spending over the last 40 years reading, math and science scores stayed stagnant.

Furthermore, the chart below shows the average scores for reading from the National NAEP exam since 1971. In 1980 the federal government made the Department of Education a Cabinet level agency and was given an annual budget. From 1980 on there are small increases in scores for the age of 17, but ages 9 and 13 actually see a drop in scores. In 2002 the Reading First Initiative was implemented which gave almost $1 Billion annually in state grants to the fund. Although the NAEP Reading assessment was revised in 2004 the chart shows only small increases in test scores for every age group despite the increased funding. With billions being added to the education fund every year, there is still no significant change in performance from students. The problem could lie with the quality of the programs our schools are spending the money they are given and not how much they are given or how large their budget is. More money is clearly not the solution.

Research suggests that schools in similar demographics outperform others even when given the same amount of money. This data demonstrates that a schools ability to effectively allocate money and resources in the areas that are most needed is more important than throwing money at the problems. Whether raising teacher’s wages, adding to technology, or just updating supplies some schools are more effective than their peers at allocating the limited amount of money they have. The chart below from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that money is primarily spent on instruction, with student support and instructional staff services largely receiving less money. If the funds allocated were more balanced among instruction, student support and instructional staff services we may see an increase in student performance.

In New Jersey, Governor Chris Christie is looking to reward schools who are using their funds effectively. He recently proposed a plan to distribute 9.1 Billion dollars equally throughout the 600 plus schools in New Jersey. Christie argues that Haddonfield with a graduation rate of 99% receives around $15,000 per student where Ashbury Park with a graduation rate of roughly 66% receives more than $33,000 per student. With these changes in place poorer schools would receive significantly less funding for the first time in 31 years, while more successful schools would receive more funding. It would effectively nullify a 1985 Supreme Court ruling that requires the state to give more funding to the 31 poorest school districts in New Jersey.

In today’s day and age there has been new technology implemented to help school districts allocate their money in a smarter, and more efficient way. The solution lies smartspend a technology that connects spending data to K-12 student performance providing a much deeper look into educational finances. smartspend works to create greater visibility in schools allowing for progress that fits their budget and ends the concept of spending because you “have it”. This software allows schools to identify correlations to show where and how the schools actual spending is used to help them do more with less. If equal spending on programs and teachers that generate good results throughout school districts becomes a common practice software such as smartspend will be the difference maker.

With so many different opinions on how we should be funding education there will always be criticism from both sides. Now, more than ever, we should let the data drive our decisions and spend on the most effective solutions. A common refrain feel that schools simply are not getting enough funds in order to help students succeed in the classroom. The opposite side argues that there is no data to support increased funding will have a positive effect on test scores and graduation rate. Are we simply not putting enough money into education or is that a scapegoat defense for how schools are spending it?